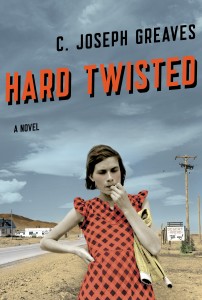

With the publication of my sophomore novel in November, an eighteen-year odyssey comes to its conclusion. I hope you’ll agree that the story behind the story of Hard Twisted is one that’s worth sharing.

With the publication of my sophomore novel in November, an eighteen-year odyssey comes to its conclusion. I hope you’ll agree that the story behind the story of Hard Twisted is one that’s worth sharing.

In November of 1994, my wife and I drove from Los Angeles to a remote bed & breakfast in southeastern Utah, where we planned to spend the Thanksgiving holiday weekend with friends from Colorado. This is America’s red-rock country – a hallucinogenic landscape of buttes and spires, mesas and gorges – and is among our nation’s most beautiful, and, paradoxically, least populous regions. It lies at the northern edge of the Navajo reservation, where the San Juan River divides Monument Valley to the south from the towns of Mexican Hat, Bluff, and Blanding to the north.

On our second day, while hiking in an area known as John’s Canyon, it began to snow. As we headed back to our car, muffled in the cottony silence, we stumbled upon two human skulls. And just as we bent to examine them, a thunderclap rolled down the canyon, shaking the ground beneath our feet.

We could see that they were Indian skulls – Navajo or Ute or Paiute, given the location. Not old enough to constitute artifacts, but not fresh enough to represent an investigable crime-scene. There was, however, definite evidence of foul play, in the form of holes or jagged fractures at the back of each skull.

Intrigued, we reported the discovery to our hosts, who in turn introduced us to a local woman named Doris Valle, who had self-published a short history of the area in and around Mexican Hat. We were not, apparently, the first hikers to find the skulls, which Doris believed were connected to a notorious double-murder mentioned in her book.

The incident occurred in 1935, when a 36-year-old sheepherder named Jimmy Palmer and his 14-year-old “child bride” whom he called Johnny Rae, newly employed by Monument Valley trading post owner Harry Goulding, clashed with some local cattlemen on whose range the Goulding sheep had trespassed. Palmer shot 77-year-old William Oliver (the former Sheriff of San Juan County) and his 25-year-old grandson Norris “Jake” Shumway, tossed both bodies into the river gorge, and then fled with Johnny Rae to Texas in a car he stole at gunpoint from Goulding. (The John’s Canyon skulls were alleged to be those of two Navajo sheepherders who were working for Goulding at the time of Palmer’s arrival.)

The story – and my rather dramatic introduction to it – haunted me long after I’d returned to my law practice in Los Angeles, and so I set out to investigate the many questions it raised. Who, exactly, was this Jimmy Palmer? Who was the girl? Where had they come from, and what had become of them?

My quest began with archived newspaper accounts of the John’s Canyon murders, from which I worked backward, following the outlaws’ trail to Texas and thence Oklahoma. The story I uncovered – via newspaper accounts, court and prison records, museum archives, site visits, and oral histories – proved more dramatic than any I could have hoped for or imagined.

The story begins in May of 1934, outside of Hugo, Oklahoma, where a homeless man and his 13-year-old daughter are befriended by a Texas drifter newly released from the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas. The drifter, James Clinton Palmer, lures father and daughter to Texas where the father, Dillard Garrett, mysteriously disappears, and where his daughter Lucile begins a one-year ordeal as Palmer’s unwilling accomplice on a crime and killing spree that traverses the Depression-era Southwest, eventually leading to the four Utah murders and culminating in Palmer’s Texas trial for the murder of Lucile’s father.

Not only was the story compelling in its own right, it contained a number of unexpectedly-intriguing elements, including (a) its Dust Bowl origins, (b) Lucile’s (aka Lottie’s, aka Johnny Rae’s) Stockholm Syndrome captivity, (c) her pregnancy and childbirth while on the run, (d) Goulding’s later fame for having introduced film director John Ford to Monument Valley in 1937, (e) Sheriff Bill Oliver’s earlier role in Posey’s War, America’s last Indian uprising, and (f) the notoriety attendant to Palmer’s 1935 Greenville, Texas “skeleton murder” trial – so called because Dillard Garrett’s remains had been placed on display at the county courthouse in Sulphur Springs – in which 14-year-old Lucile would be the State’s star witness against her captor.

Having finally unearthed the story, I turned next to crafting it into a novel, a process that took around two years, and that I finally completed in 2009. Happily, while still in manuscript, Hard Twisted was named Best Historical Novel in the 2010 SouthWest Writers International Writing Contest, and was soon sold to Bloomsbury, which then selected it as one of nine international novels with which to launch their new, all-literary Bloomsbury Circus imprint in the UK.

On November 13, 2012, the saga of Clint Palmer and Lottie Garrett will be available in bookstores worldwide, and the circle that began for me in 1994 on a snowy, windswept day in John’s Canyon, Utah will finally be complete.

I hope you’ll like the book.

Clinton Palmer was my grandfathers step brother. Garret was killed on my families land. Look forward to reading this book.

Chuck,

You may (or may not) remember me from the Writers and Scribblers meet in Durango – I am the photographer who cannot write his own name! hahahaha.

John’s Canyon is of particular interest to me, I am looking forward to Hard Twisted. I have quite a collection of photographs from the canyon and surrounding area – mostly rock art and some landscapes. John’s Canyon was my place of choice in the days when a 5 day fast was necessary occasionally.

regards,

David

PS, don’t know which is worse, my typing or spelling . . .forgive.