It speaks to the rich tradition of Penn State athletics that one of the most extraordinary sportsmen of his day – and to this day, the only NFL veteran ever to fight and defeat a world heavyweight boxing champion – today is all but unknown except to a few diehard fans. It took a chance remark overheard at a family wedding for me to learn that Steven Vincent Hamas, my great-uncle, had once been “a boxer.” What I learned after researching his story is that he was so much more than that.

A boomtown of factories and textile mills in the decades surrounding the first World War, Passaic, New Jersey had been a city of immigrants ever since its formation by Dutch settlers in the seventeenth century. Its polyglot culture and blue-collar ethos made Passaic an ideal location for Austro-Hungarian immigrant Andrew Hamas (HAY-mus) to pursue his American dream. Two of the virtues Andrew instilled in his seven children were Eastern Rite Catholicism and a passion for all things athletic. The vacant lot next to the Hamas Tavern on Third Street boasted Passaic’s first outdoor basketball hoop, and it was there that the Hamas boys – Michael, Steven, Andrew, George, and John – honed their games while challenging all comers.

Both Steve (born January 9, 1907) and his older brother Michael played on Passaic High’s storied “Wonder Teams” of 1919-1925 that won 159 straight games – a boys’ varsity record that stands to this day – with Mike averaging 31.1 points per game in a low-scoring era in which teams still jumped center-tap after every bucket. Mike went on to captain the Penn State basketball squad, but it was kid brother Steve who would well and truly put the Hamas clan on the national sporting map.

Steve followed Mike to Happy Valley, matriculating in the fall of 1925. A mathematical savant, Steve was a pre-med major with dreams of becoming a surgeon. But it was in sports that the 6-1, 190-pounder truly shined, earning 12 varsity letters – still a school record – in football, basketball, boxing, track, and lacrosse while winning Penn State’s inaugural Outstanding Athlete Award.

Steve later recounted his introduction to boxing to sportswriter Mike Gelos of the Passaic Herald News. After the 1926-27 basketball season had ended, boxing coach Leo Hauck pulled the strapping sophomore forward aside. The Penn State fighters were prepping for the Intercollegiate Boxing Association tournament in Syracuse and were in desperate need of a heavyweight. Might Steve be willing to go a few rounds with his Varsity Hall roommate Marty McAndrew, the intercollegiate light-heavyweight champ? “Figuring his roommate wouldn’t hit him too hard or too often, Hamas agreed,” Gelos recalled, “and managed to survive the sparring session. He thanked McAndrew for allowing him to stay vertical, to which his buddy replied, ‘Steve, I really tried to knock your block off.’”

Steve “Hurricane” Hamas won the collegiate heavyweight crown that year, pacing the Nittany Lions to Houck’s second national team title. Both would repeat as national champions in 1929, Steve’s senior season. Penn State would win two more national titles under Houck, in 1930 and 1932, but Steve Hamas by then had brought his unique blend of talents to an entirely different arena.

Hamas was back in Passaic after graduation, teaching and putting money aside for medical school when an intriguing opportunity presented itself. Edwin (Piggy) Simandl, a wholesale meat salesman from nearby Orange, had acquired franchise rights to the Duluth Eskimos of the fledgling National Football League and was assembling a squad for the 1929 season. Might the versatile Hamas, who’d just set a Penn State record by earning five varsity letters in his senior season, like to try the professional game?

The Orange (N.J.) Tornadoes made their NFL debut on September 29, 1929 before 9,000 mostly curious onlookers at Orange’s Knights of Columbus Stadium. With the hard-hitting Hamas at fullback, the Tornadoes battled Tim Mara’s New York Football Giants to a scoreless draw, the result sealed by Hamas’ game-saving tackle on a 55-yard Ray Flaherty interception return.

A shaggy forebear of today’s NFL, the league in 1929 was a roving carnival of cash-strapped owners and itinerant gridders bent on reliving their collegiate glories. Attendance was sparse, and stability elusive. The Giants of 1929, for example, had just merged with the Detroit Wolverines of 1928, one of three teams that had folded that offseason. Giants quarterback Benny Friedman, the former Michigan All-American, was the league’s highest-paid player not named Red Grange. He earned $750 per game.

With a respectable record of 3-5-4, the Tornadoes tied for sixth in the 12-team league even as Curly Lambeau’s 12-0-1 Green Bay Packers claimed their first NFL title. And while this would be Hamas’ only season of professional football, he got to stand toe-to-toe with such future NFL Hall of Famers as Friedman, Ernie Nevers of the Chicago Cardinals, and Jimmy Conzelman of the Providence Steam Roller. As for the Tornadoes, they would be sold after the 1930 season and, after passing through Cleveland (as the Indians) and Boston (as the Braves), would eventually become the Washington Redskins, now the Commanders.

With money still tight and the world economy in ruins, Steve Hamas, newly married to the former Katheryn Work, took stock of his prospects. Heavyweight champ Gene Tunney had retired from boxing in 1928, and Jack Sharkey had just lost the vacant title to German bruiser Max Schmeling. As a two-time national collegiate champion, Steve reasoned he at least could earn more in the ring than on the gridiron. He called Houck, his old college coach, who put him in touch with veteran fight manager Charley Harvey.

Fighting mostly in Newark, Hamas won his first seven professional bouts, five by knockout. He won his next nine on a West Coast swing before returning east to make his Madison Square Garden debut on May 15, 1931 in an undercard bout against Al Moro, scoring a second-round knockout. Nine more victories followed, giving him nineteen straight by knockout before finally going the distance against veteran Hans Birke at the Garden for his 27th professional win.

Steve’s unblemished record, and the crushing left hook behind it, did not go unnoticed. His next fight, scheduled for January 15, 1932 at Madison Square Garden, would determine whether the newly-anointed “Passaic Pounder” was worthy of the nickname. Tommy Loughran, considered one of the greatest pure boxers of that or any era, had been world light-heavyweight champion with over a hundred professional victories to his credit, including unanimous decisions over James J. Braddock and Max Baer. A win over Loughran, twice named The Ring magazine’s Fighter of the Year, would catapult Steve Hamas from fistic obscurity into the ranks of the heavyweight elite.

Hamas’ second-round upset of Loughran, followed by a career-ending knockout of Armand Emanuel, put his record at 29-0. He then suffered his first professional loss, on points, to the slick-boxing Lee Ramage for the California State heavyweight title. Serial rematches against Loughran (a win and two losses) and Ramage (two wins and a draw), plus a draw with Charley Masseria and a fourth-round KO of Benny Miller, set the stage for what would prove to be the high point of Steve’s boxing career.

Atop the heavyweight division, anarchy reigned. Schmeling had defended his title but once before losing it to Sharkey in June of 1932. Sharkey had, in turn, lost to Italian giant Primo Carnera the following year. Schmeling’s first attempt at a comeback had been thwarted by Baer. Sharkey, meanwhile, had fallen to Loughran. For Hamas, earning a title shot meant again besting one of these top-tier contenders. So when Charley Harvey reached an agreement with Schmeling’s manager Joe Jacobs for a February, 1934 bout in Philadelphia, Hamas prepared as never before.

Working with Newark trainer Al Thoma, Hamas spent hours sparring and studying film, dissecting the big German’s style. An effective counterpuncher, Schmeling relied on a straight right hand that he always held at the ready, high and tight to his chest. This short, powerful punch was the perfect counter to Hamas’ best weapon, the left hook. Always a cerebral fighter, Hamas settled on a strategy of fighting from a crouch to frustrate Schmeling and elude that powerful right.

Before a capacity crowd of 15,000 at Philadelphia’s Convention Hall on February 13, 1934, Hamas deployed that strategy to perfection, crouching and weaving and tattooing the former champion with stiff jabs to the face. By the ninth round he’d opened a gash over Schmeling’s left eye. Blind and bleeding and never able to unload, Max Schmeling, the 12-to-5 favorite, barely stayed upright through 12 punishing rounds to lose by unanimous decision.

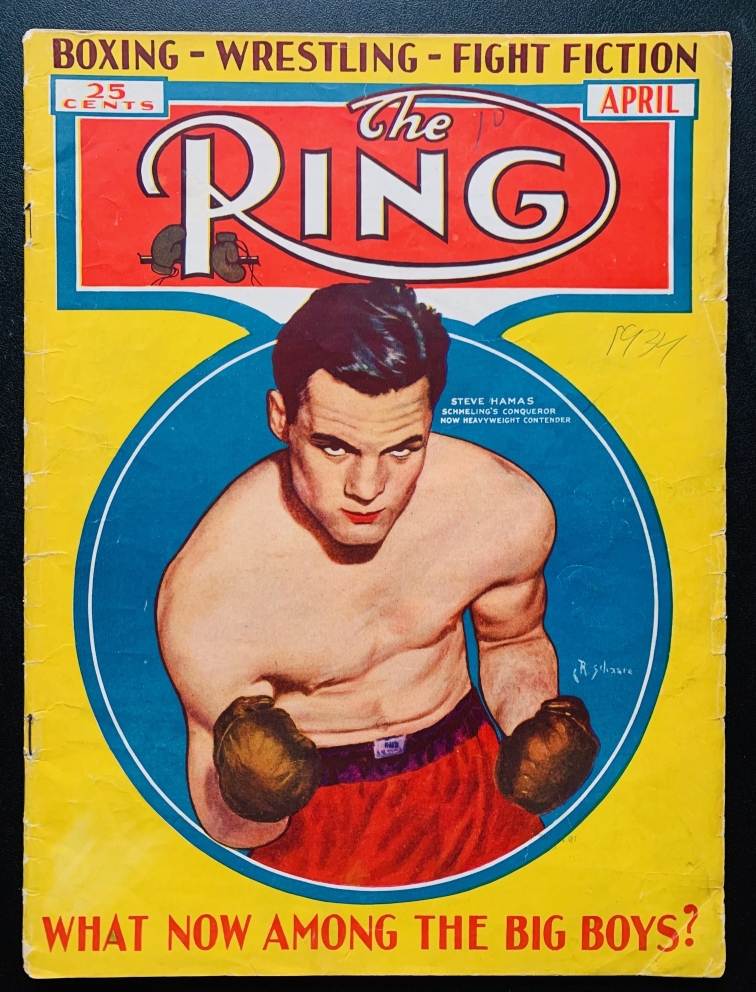

Hamas had begun the 1934 campaign ranked ninth in the world. His win in Philadelphia landed him on the April cover of The Ring alongside the tagline “Schmeling’s Conqueror Now Heavyweight Contender.” Two months later, Baer beat Carnera for the title. In October, Hamas took a split decision off the dangerous Art Lasky at Madison Square Garden and entered 1935 right where he wanted to be: as the top-ranked contender for Baer’s world heavyweight crown.

Contracts with Madison Square Garden for the Hamas-Lasky fight guaranteed the winner a title shot against Baer. The fight, however, had proved controversial when a backhand blow by Lasky was penalized by referee Billy Cavanaugh. Although Lasky’s post-fight appeal was denied, the Garden’s all-powerful matchmaker, Jimmy Johnston, decreed a Hamas-Lasky rematch. That edict outraged Charley Harvey, who instead accepted a guaranteed $25,000 purse – roughly $500,000 in today’s dollars – offered by German promoter Walter Rothenburg if Hamas would travel to Hamburg for a rematch with Schmeling. In response, Johnston threatened suit to enjoin Hamas from ever again fighting stateside.

In retrospect, Harvey’s decision was, as The Ring’s Ted Carroll would later call it, “one of the most ruinous moves ever made by a fight manager.” Worse yet, Hamas had suffered an injury to his left elbow during training but, rather than risk the Schmeling purse and reprisal from Johnston, Harvey refused to postpone. Unable to spar, Hamas was limited to roadwork and limbering exercises – preparations that appeared lackadaisical to the sporting press and were mistaken for overconfidence. Meanwhile, with the Third Reich’s pride on the line, Rothenburg had constructed Hanseatic Hall, a 25,000-seat indoor arena – Europe’s largest – just for the fight.

On March 10, 1935, Hamas and Schmeling again met under the lights before a sellout crowd with both of their futures at stake. This time, however, after feeling a pop in his injured elbow during the third round, Hamas was all but defenseless against the German champion’s powerful right hand. He suffered six knockdowns in total, three in the sixth round alone, and would have no memory of the fight’s dramatic finale when, battling on instinct, he refused to go down under a terrible onslaught of punches.

The next day’s banner headline in the Philadelphia Record, SCHMELING STOPS HAMAS IN 9TH ROUND, didn’t begin to capture the carnage. So savage was the beating he’d endured that Hamas would spend 10 days in a Berlin hospital, partially paralyzed and seeing double. Katheryn, who generally shunned her husband’s fights but who’d traveled to Hamburg for this one, had seen enough – an assessment with which Hamas reluctantly agreed. And while Hamas-Schmeling II was to be the Passaic Pounder’s last bout, its fallout would continue to reverberate for years to come, on both sides of the Atlantic.

As fate would have it, neither Schmeling nor Lasky got the coveted title shot against Baer. Instead that honor fell to Braddock, a 10-to-1 underdog whom history would immortalize as the “Cinderella Man” for his hardscrabble past and his stunning upset victory.

In Germany, meanwhile, trouble was brewing for Schmeling. At the conclusion of the Hamas fight, as 25,000 delirious fans sang the Deutschlandied, Joe Jacobs, Schmeling’s Jewish manager, could clearly be seen with his arm outstretched, giving the Nazi salute. Schmeling was promptly summoned to the office of Nazi Reichssportführer Hans von Tschammer, who ordered the fighter to sever all ties with Jacobs, which Schmeling refused. While a principled stance, it was one for which Schmeling nearly paid with his life when, unlike other prominent German artists, actors, and athletes, he was later drafted and sent to the front lines during World War II.

Schmeling’s 1935 win over Hamas had revived the 30-year-old German’s hope of recapturing the heavyweight crown now held by Braddock. To get there, however, he would first have to face boxing’s newest sensation, an unbeaten 21-year-old Detroit heavyweight named Joe Louis. “Steve Hamas had driven me crazy in Philadelphia by using an outstanding eye to pull away from my right,” Schmeling would write in his 1977 autobiography. “Even though I hit him countless times, the effect of the punches was diminished. So I had to use a similar move to try to neutralize some of the deadly impact of the Brown Bomber’s powerful rights.” Ripping that page from the Hamas playbook, Schmeling crouched and jabbed and generally frustrated Louis for eleven tactical rounds before scoring a stunning 12th-round knockout at Yankee Stadium on June 19, 1936, ending Louis’ unbeaten streak at 24. In their 1938 rematch, Louis turned the tables on Schmeling with a first-round knockout in what remains the most famous bout in all boxing history.

Steve Hamas never made it to medical school. He did, however, serve his country with honor as a major in the Army Air Corps during the Second World War before becoming the mayor of Wallington, N.J. and being inducted into the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame. He also became an outspoken critic of boxing. “The referee can’t always tell how bad a man is hurt,” he told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1957. “A man can take a brutal beating in the ring and perhaps be injured for life.”

In his later years, Hamas would author an unpublished novel, Glorious Dissipation, and would return to the Penn State campus with his collie dog Laddie to perform mathematical demonstrations. Steven Hamas III recalls that his grandfather would “play games with the audience that his dog could multiply faster than they could. Someone would choose any number times any number and before the students could use the hand crank on their comptometers, he would have Laddie whisper the answer, leaving them dumbfounded.”

With a career record of 35-4-2, including 27 by knockout, Hamas could boast of having beaten the only three fighters – Loughran, Ramage, and Schmeling – who’d ever beaten him. But even the Passaic Pounder was overmatched against Guillain-Barré Syndrome, which claimed Penn State’s all-time letterman on October 10, 1974. He was survived by Katheryn, and by their children, Steven, Jr. and Katheryn Ann.

So yes, my great-uncle was a boxer. He was also a pioneer, a polymath, and a patriot who carried the hopes of a nation across the Atlantic to battle Nazi Germany by proxy more than a year ahead of the 1936 Berlin Olympiad. For all these reasons, Steve Hamas should be remembered, and perhaps even revered, as one of the greatest Nittany Lions.

This article by Chuck Greaves first appeared in the March/April 2019 issue of Penn Stater, the official alumni magazine of Penn State University.