On November 12, 1934, a peripatetic young artist named Everett Ruess loaded up his pack burros, said goodbye to the friends he’d made in the remote Mormon settlement of Escalante, Utah, and resumed a journey of exploration – both cartographic and spiritual – that had come to define his young life. His intention, as expressed in letters he’d posted to his family in California, was to travel south – either across the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry and back onto the Navajo reservation from which he’d come, or else into the maze of side canyons marking the Escalante River’s confluence with the Colorado, and thence eastward, crossing the latter somewhere above its junction with the San Juan River gorge.

He was never heard from again.

That same day, less than fifty miles to the east, a 36-year-old Texas drifter named James Clinton Palmer was building a crude dugout shelter in which to spend the coming winter in the company of a ragged, visibly-pregnant 14-year-old whom he called Johnny Rae. The disquieting couple had been hired by Monument Valley trading-post owner Harry Goulding to tend a flock of sheep that had, just a few months earlier, been ordered north of the San Juan River by federal authorities when their home range became part of the Navajo reservation in 1933. Not surprisingly, this sudden influx of over 1,500 hungry sheep precipitated a series of escalating conflicts with the Mormon cattlemen on whose traditional stock range the Goulding sheep now foraged.

What Goulding did not know was that the man he’d hired was a violent psychopath recently released from the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas. Or that Palmer had, only a few months earlier, kidnapped his child bride – whose real name was Lucile “Lottie” Garrett – from Oklahoma after murdering her father. Or that Palmer would soon be murdering again, in spectacular fashion.

The red rock country of southern Utah – with its canyons and mesas, its spires and gorges – is among the most beautiful and, paradoxically, among the least populous regions in America, and when Everett Ruess vanished into its rugged dreamscape in November of 1934, he passed into legend. No fewer than five books and two documentary films have celebrated the young man Wallace Stegner called an “atavistic wanderer of the wastelands,” and about whom John Nichols wrote, “it was his life that was his greatest work of art.” His disappearance remains – along with those of Amelia Earhart and Joseph Force Crater – one of the enduring mysteries of the Twentieth Century.

Speculation over the fate of Everett Ruess has run rampant ever since his pack burros and a few personal effects were discovered in remote Davis Gulch – northwest of the Colorado River’s confluence with the San Juan River – on March 3, 1935. Searchers soon discovered his trademark “NEMO 1934” graffito etched into the high-desert sandstone of a nearby Anasazi ruin. Of the boy, however, there was no further sign.

Theories advanced to explain the Ruess mystery have ranged from the prosaic – he fell to his death, or he drowned – to the fantastic. Some say he was murdered, or took his own life. Some say he never died at all, but rather slipped onto the Navajo reservation, took a native bride, and lived to old age in quiet anonymity. In April of 2009, National Geographic magazine entered the fray, reporting a Navajo grandparent’s supposed deathbed account of Everett Ruess’s murder at the hands of three Ute Indian assailants. Initial DNA testing of skeletal remains raised hopes that the 75-year mystery had at last been solved. Those hopes were dashed, however, when further testing confirmed the purported Ruess remains to be of Navajo ancestry.

There is, however, one solid clue to the fate of Everett Ruess, which came to public light in 1983 when Escalante river guide Ken Slight (the real-life inspiration for Seldom Seen Smith, of The Monkey Wrench Gang fame) found another NEMO etching in lower Grand Gulch, also north of the San Juan River, some forty miles due east of the 1934 Davis Gulch discovery. According to Southwest author and historian Fred Blackburn, who personally took tracings of the two graffiti, they indicate a common hand.

If Ruess was, in fact, hiking eastward, exploring the cuts and canyons along the northern rim of the San Juan River gorge, perhaps working his way toward the bridge crossing at Mexican Hat, then he soon would have entered John’s Canyon, less than ten miles due east of Grand Gulch, probably in late November or early December of 1934.

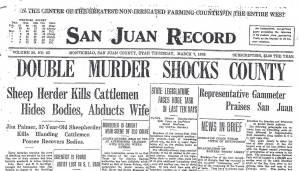

[Full Scan of San Juan Record from March 7, 1935]

And there he would almost certainly have encountered Clint Palmer.

By Thanksgiving of 1934, complications in young Lucile’s pregnancy required that she return to Goulding’s Trading Post in Monument Valley, where she remained until December 11 and then was moved to Monticello, Utah, giving birth on December 31 to a baby boy who would die seven days later. By mid-January, she and Palmer were back in their John’s Canyon dugout, and the long-simmering range war over the Goulding sheep would soon come to a boil.

On February 28, 1935, as Palmer once again drove the Goulding flock into John’s Canyon for water, he encountered Blanding cattleman William E. Oliver, age 77, the former Sheriff of San Juan County, Utah. Oliver was one of – and arguably the last of – the legendary frontier lawmen, thanks to his central role in Posey’s War, America’s last Indian uprising. In that 1923 incident, Sheriff Oliver’s horse was shot out from under him during a daring escape attempt by a pair of Ute Indian prisoners, in response to which Oliver held over 40 Ute men, women and children hostage in a Blanding stockade in a tense, month-long armed standoff.

Bill Oliver was not, even in retirement, a man to be trifled with.

Inside John’s Canyon, words were exchanged between Palmer and Oliver, and shots were fired, and the former Sheriff fell dead beside his horse. After dragging Oliver’s body to the river gorge, Palmer set off on horseback to find Norris Shumway, Oliver’s 25-year-old grandson, whom Palmer then shot and decapitated, eliminating his only potential witness.

The next day, Palmer and Lottie appeared in Monument Valley, where at gunpoint they relieved Harry Goulding of his car and forty dollars in cash before lighting out for Texas. Unbeknownst to the fleeing outlaws, however, the decapitated skeleton of Lucile’s father had since been discovered and placed on display at the Hopkins County courthouse in Sulphur Springs, and a Texas warrant was outstanding for Palmer’s arrest. The pair was finally apprehended on March 5, 1935, and the resulting Greenville, Texas “skeleton murder” trial – featuring Lucile Garrett as its star witness – was a regional sensation.

According to this blood-soaked timeline, Clint Palmer – already psychotic and heavily-armed, and under growing pressure from all sides – was alone in Utah’s John’s Canyon from Thanksgiving of 1934 until mid-January of 1935. Did Everett Ruess – whom we now believe to have been but ten miles away, and heading in Palmer’s direction – wander into Palmer’s sheep camp? And if so, did he meet the same fate as would soon befall Oliver and Shumway?

On the same day – March 7, 1935 – that the San Juan Record first reported the John’s Canyon killings in a banner headline proclaiming DOUBLE MURDER SHOCKS COUNTY, it also reported, in the adjoining column on page one, the disappearance of a young, unnamed artist who had last been seen in November of 1934 near the Escalante River, where “[p]lanes were used to try and locate the artist’s camp and succeeded in finding what they thought to be the pack burrow [sic] which he used. No camp or other sign of the lost man have yet been found.”

Harry Goulding is today best known as the man who brought Hollywood to Monument Valley when, in 1937, he drove his battered truck to Los Angeles with a bedroll and a stack of photographs and managed to convince director John Ford to film Stagecoach – a planned Western epic starring a young stuntman named John Wayne – on a Navajo reservation reeling from a half-decade of drought and Depression.

Pioneer, promoter, and trading post impresario, Goulding was a Western character writ large whose life has been chronicled in books like Samuel Moon’s Tall Sheep (1992), and Richard E. Klinck’s Land of Room Enough and Time Enough (1995), and most recently in the March, 2009 issue of Vanity Fair magazine (Bissinger, “Inventing Ford Country.”) But there is one subject on which even the loquacious Harry Goulding would remain forever silent, right up until his death in 1981:

“Harry never defended himself to the people of Blanding, and forty years later he would not speak to me on the record about his part in the Jimmy Palmer affair. True to his western values, he believed that a man should be judged by his actions, not by his words, and that his life would have to speak for him. Ultimately, it seems that we must leave it where Harry wanted us to leave it.” Moon, Tall Sheep, at 87.

In contrast to the gauzy glow of legend that has come to envelop Everett Ruess, the John’s Canyon murders of Bill Oliver and Norris Shumway are but forgotten footnotes in the long and occasionally colorful history of San Juan County, Utah. In November of 1994, however, I stumbled upon a pair of human skulls while hiking in John’s Canyon. That discovery would lead me to undertake years of painstaking research into the John’s Canyon murders, their etiology and consequences – research that grew to encompass newspaper accounts, court and prison records, genealogical and oral histories, and (in the archives of a Salt Lake City museum) re-discovery of the “lost” 1935 grand jury testimony of Harry Goulding.

My novel Hard Twisted – the true story of Lottie Garrett’s harrowing year in captivity – was published by Bloomsbury on November 13, 2012. It opens the door on a long-forgotten chapter in Western history. Does it also hold a clue to the seemingly insoluble mystery of Everett Ruess?

I have read that western mistery history with great interest, I was six years old when I saw the Stagecoach of John Ford with my Dad. I enjoyed the spectacular landscape, it was one of the last USA movies that italian could see, after came Second War War and the censorship about USA movies. Thank You

In David Roberts’ book, it is actually possible to prove Aneth’s story, it goes like this; He (Aneth) did come back with a lock of blond hair. So the body is a Ute, what one should be looking for is a Ute who was around 1934 but not in 1935. One with a Social Security # who is’nt on the SSDI. ….. Fortunately, there are recorded lists from both groups of Utes made 1934-1935 With annotations. I could’nt research them (no funds) but they should show a missing 20 something year old. ….. If you have that, you have a possible DNA match + verification of Aneths’ story. ….. One hour + out and back (with time for exumation) If Aneth had hair, he buried that boy deep. … He’s still there. …. All you need is a Magnotometer and time.

Fascinating story. Would make a great movie. Palmer, Goulding, Lottie, Ruess. What ever happened to Lottie, after being released at age 21?

What do we make of Aneth’s story, now that it has been proven the skeleton everybody thought was Ruess was actually a Navajo?

Could still be true, and Ruess is resting in another crevice nearby. Or he made it all up? Or he witnessed the murder of another young white man by the Utes?

Lottie married in 1941, and had a son she named Dillard. She died in 1991.

You found two skulls, eh?

Was their DNA screened?

What are the results?

May be an ignorant question, but I just watched a Mysterious at the Monument segment on Ruess, and they portrayed his two Burros as being alive. How could that be, after all that time, being tied up? Thank you

They were found alive. My understanding is that they were not tied up, but rather contained by a brush fence in an area with sufficient forage.